We got up early and drove to Plymouth - about half of the way back to Boston - to visit Plimoth Plantation . No, that's not a misspelling - The Plantation is a living history center, depicting the lives of the Pilgrims of Plymouth Colony (w) in the early 17th century. In those days, no one cared much about "correct" spelling, and the name of the colony was spelled various different ways. The Plantation settled on "Plimoth" to distinguish it from the modern day town of Plymouth.

The interesting thing about Plimoth Plantation, and the thing that sets it apart from other living history establishments such as Colonial Williamsburg, is that the "inhabitants" of the village speak in 17th century English. If you try to ask them about anything that didn't exist in their time, they won't know what you're talking about. And if you do something modern, like take their picture, or talk on your cell phone, they'll just pretend not to notice.

On the drive, we passed a flock of wild turkeys:

Here's the entrance to the Plantation:

The Plantation consists of three separate sections. After stopping at the Visitor Center and watching a short introductory film presentation, we proceeded down a path through the woods:

...to the first section, the Wampanoag Homesite. This is a recreation of a Wampanoag (w) American Indian village. The "residents" of this village dress in period costumes, but speak in 21st century English. Here are some pictures:

A Wampanoag hut

Inside the hut

An animal skin laid out to dry in the sun

A canoe made from a hollowed out log

A canoe in progress - it's hollowed out by burning

A longhouse

Inside the longhouse

In those last two pictures, you can see two Native American women. They were talking to the visitors and answering questions, although as it turned out, they were not actually Wampanoag themselves.

In the first of those two pictures, you can see a metal pan with several small round cakes. I asked about them, and was told they were ash cakes. No, not cakes made from ashes, but cakes baked in or over hot ashes. I asked if they were available for tasting and was told no, first because they're not allowed to let visitors eat them due to health regulations, and second because they hadn't been baked yet!

The next stop was the Craft Center, where Plantation workers demonstrated various crafts from the period, including:

Spinning wool

Weaving cloth

Making candles

Baking bread

The bread in that last picture was baked in the brick oven behind it. Unlike the ash cakes, this bread was available for human consumption, and it was delicious.

While at the Craft Center, I used the restroom, and was intrigued by these pictures on the wall. Apparently, removal of facial hair was much more difficult - and painful - in olden days:

And then, at last, we came to Plimoth Village itself. After we passed through the main gate:

... the first thing we came to was the Meeting House:

We went upstairs, and found cannons, for defense of the colony:

...and a good vantage point for an overall view of the village:

We visited several houses:

...one of which had a garden in the back:

Notice that the house in the first picture has a nameplate reading "Standish," referring, of course, to the well known historical figure Myles Standish (w). Mr. Standish was not at home, but when we visited another house, we found him there:

Terry, linguist that she is, entertained herself (and me) by speaking to the residents in their own language. In addition to Myles Standish, we spoke to another man who was using a small hatchet to carve a spoon out of a block of wood, and a young woman tending a pot of stew. Terry asked the woman what was in the stew, and she rattled off a list of ingredients, which unfortunately I don't remember. When Terry asked if the stew contained potatoes, the woman replied "I don't know what they are." I commented to Terry later that the woman played her part well, but her nose piercing sort of detracted from the effect.

Another visitor asked the man carving the spoon if it was to eat with. He responded that of course you didn't eat with a spoon, you used it to ladle out soup from a pot (it was a large block of wood, so it would have been a large spoon). When the woman said that she did eat with a spoon, he answered "You must be French!"

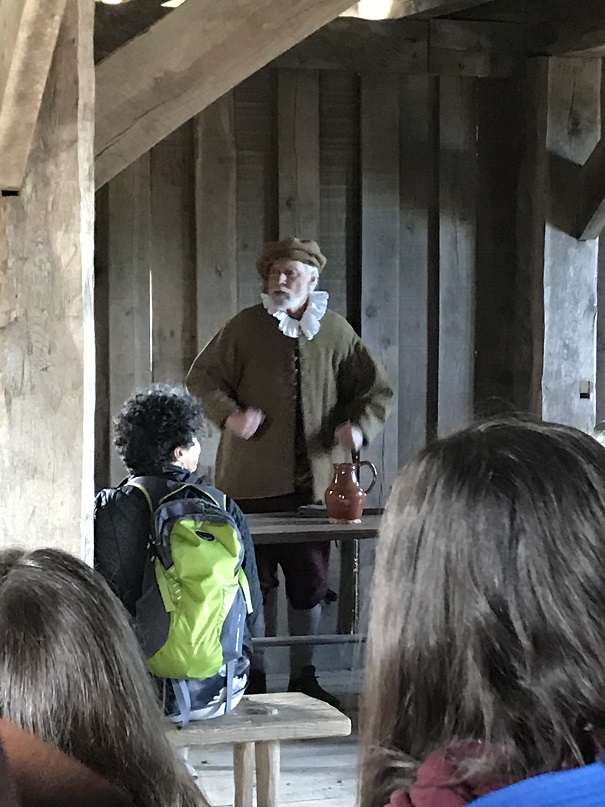

At about this time, we were joined by Nanda and Jose. Oh, didn't I mention them? Nanda (short for Fernanda) is a friend that Terry met on one of her WhatsApp groups, and Jose is her husband. They're from Brazil, but now they live in the Boston area. So Terry arranged for them to come down and meet us. Anyway, just as they arrived, a man with a drum stepped out into the village square and began to beat on the drum and shout "Oyez! Oyez!" several times, until every one - residents and visitors alike - gathered in the square. Then a man, who turned out to be the local preacher, told us that since it was Sunday, the residents were going to gather in the meeting house for a service, and we visitors were cordially invited to join them. So we all walked up to the meeting house, where the preacher...

...gave a brief talk on the Puritans and their beliefs, with many disparaging remarks about the Church of England and the King James Bible. Yes, the Puritans didn't approve of that new-fangled King James translation, preferring the more traditional Geneva Bible. (After I got home, I looked at the Geneva Bible, and decided that from a 21st century perspective, there's not much difference - they're both equally challenging.) He also led us in singing a Psalm - specifically, the first stanza of Psalm 100, sung to the tune known as Old 100th (w). You know that tune, even if you don't think you do. You might know it as the Doxology, or "Praise God, from whom all blessings flow."

After church, we all went back to the visitor center for lunch. The cafe, in addition to the usual assortment of contemporary fare, also offers typical dishes of the 17th century. Terry had potage, a kind of stew, and a sallet, better known as salad these days. My lunch included succotash. When I was growing up, succotash was a mixture of lima beans and corn; and in fact, Wikipedia defines it as "a food dish consisting primarily of sweet corn with lima beans or other shell beans." This succotash, however, consisted of what appeared to be some kind of squash mixed with cranberries. Normally, I don't care for squash, but I'll eat just about anything if you mix it with cranberries. Whatever, it was good.

After lunch, Jose and I puttered around in the gift shop. I bought a 2019 calendar for my office, and (of course) a CD. The CD is by a group called Penny Merriment, and is called English Songs From the Time Of The Pilgrims. We've listened to it a couple of times since coming home, and it's charming, with wonderful vocal harmonies. It also has a fascinating variation on the song Three Blind Mice. It's definitely not the one we all grew up with. In the first place, it's in a minor key. And the lyrics are strange:

Three Blinde Mice, Three Blinde Mice, Dame Iulian, Dame Iulian The Miller and his merry olde Wife, She scrapte her tripe licke thou the knife.

"Iulian" is pronounced "Julianne." And if anyone can shed any light on the meaning of that last line, and explain what it has to do with blind mice, I'd be profoundly grateful!

We said goodbye to Nanda and Jose and proceeded into Plymouth to visit the Plimoth Grist Mill (w). This mill, which is also run by the Plimoth Plantation, is a restored, and still functional, corn grinding mill, standing on the site of the original mill, which dates back to 1636. We didn't get to watch them grind any corn, because by the time we got there, they were just closing down for the day. But I did get pictures.

The process starts here, where the dried corn kernels are poured into the hopper, and are ground between the two large millstones (you can only see the top stone in this picture). On the rail in the foreground, you can see some kernels, and a little bit of ground corn.

Downstairs, you can see the mechanism which turns the millstones. The large axle in the middle is connected to the water wheel outside, which is turned by the running water of the stream. The axle turns the large gear, which turns the small gear, which turns the stones.

Notice the chute (behind the man in the blue shirt), through which the ground corn falls down to these collection bins:

Then it gets sifted, and the finer particles are bagged up and sold as corn meal:

...while the larger particles become grits. Here's a picture of the water wheel from the outside:

Before we left, we bought a bag of corn meal - no, not one of the large bags in the picture, just a normal one pound bag. As of this writing, we haven't done anything with it yet.

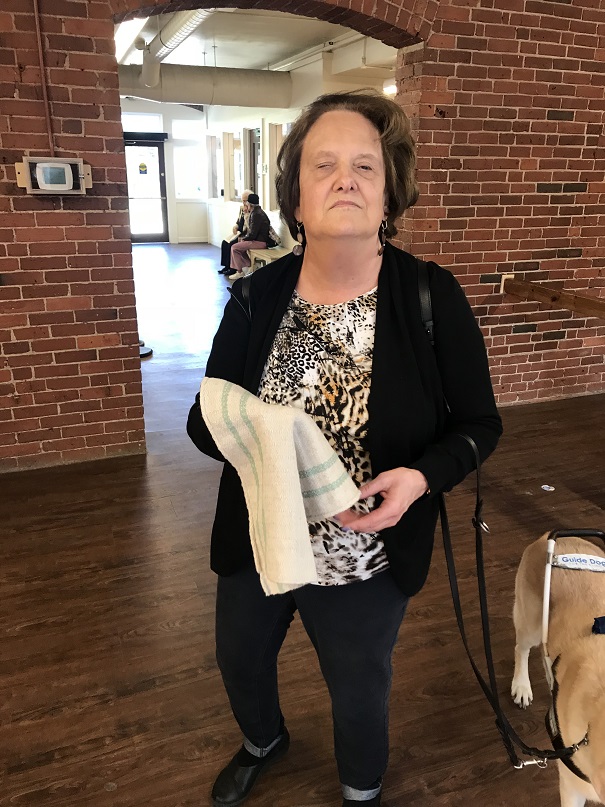

Well, of course, you can't go all the way across the country to Plymouth, Massachusetts, and not go to see Plymouth Rock (w). So of course, we did. I did, anyway. Terry stayed in the car. You can't get close enough to the rock to touch it, so she figured there was no point.

The rock is sheltered by this monument:

...and here it is, the Rock itself:

Not much to look at, is it? Plymouth Rock is, after all.... just a big rock. Actually, it used to be much bigger. According to the park ranger at the site (and the Wikipedia article), it broke into two pieces when they tried to move it, back in 1774, and the top half was in a museum until it was moved back to its original location in 1880. Over the years, many people chipped off pieces for souvenirs, so what's left is considerably less than it once was. Also, quite a bit of it is buried under the sand.

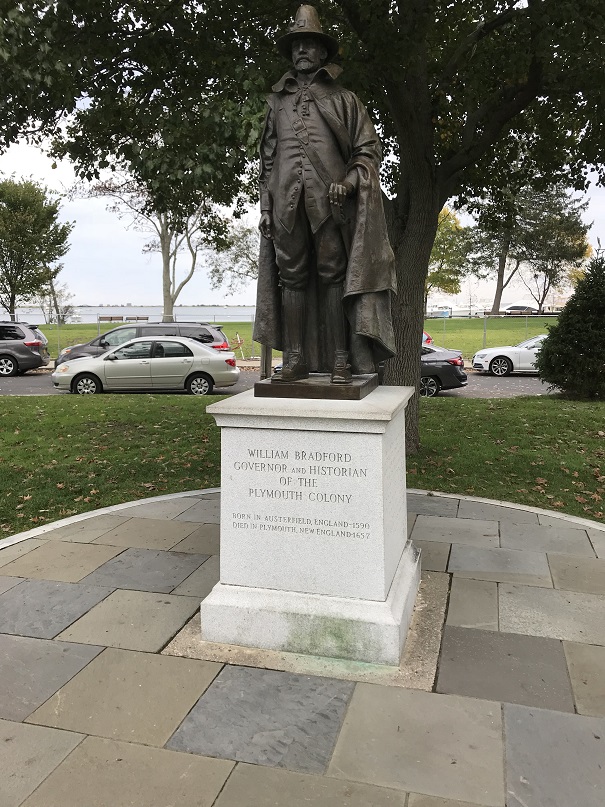

Just up the street from the Rock, I stopped to take a look at this statue of William Bradford (w), five time Governor of Plymouth Colony

We had dinner at a very nice seafood restaurant in Plymouth, and then drove back to the resort, stopping to pick up a few groceries. The idea was to save a little money by eating breakfasts in our room before going out each day.

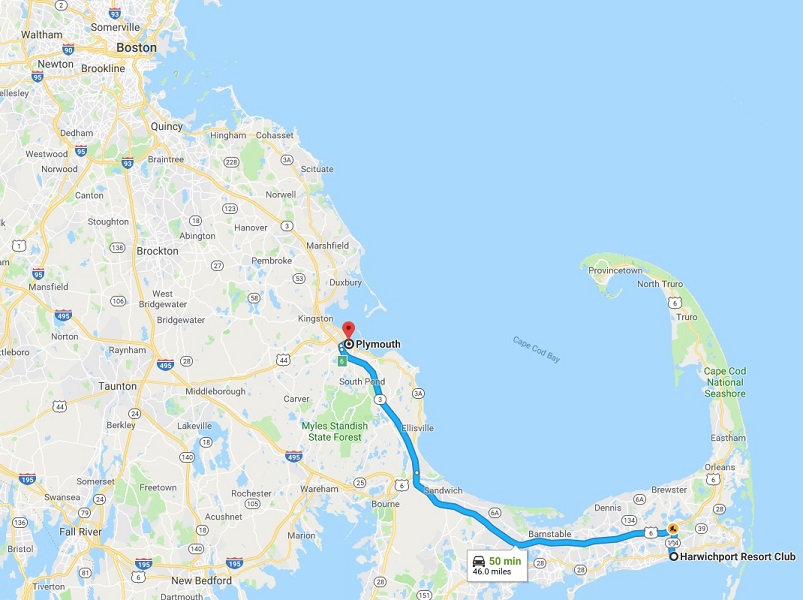

Here's a map of the day's wanderings: